Click play to listen to this article.

Either you learn to manage your emotions after a breakup, or they’ll manage you.

They can make you chase after your ex, stalk them on social media, and obsess over them — all of which only prolongs your healing. At worst, your emotions inspire you to get batshit drunk one night and curse your ex out, only to get beaten up bloody by their over-protective roided-out brother the next day.

Since none of us want to end up prolonging our healing or getting beaten to a pulp, here’s one way of managing your emotions better. Just beware that this is a hair-brained theory of mine. It’s not a psychological model put together by any researcher that I know of. So, by no means take it as gospel.

A guide to breakup recovery based on embracing discomfort, extracting wisdom from dark moments, and healing through evidence-based practices.

Order Your CopyModel Of Competency

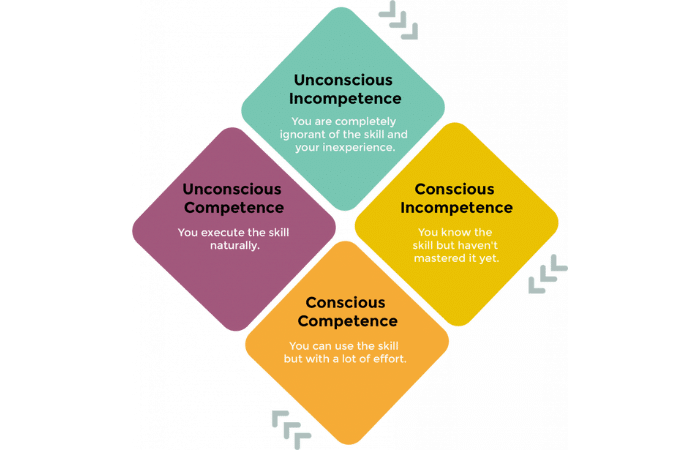

There’s a famous grid in Neuro-Linguistic Programming that people like to refer to when they want to state the obvious in a way that sounds really smart.

It looks something like this:

This grid is used in regard to learning new skills. Take a skill, let’s say cooking. Everyone starts out at unconscious incompetence. That is, not only are you unable to cook, but you’re unaware of what is required to cook.

From there, you become consciously incompetent. You learn that you suck at braising, that you’re horrible at plating your dishes, and that you don’t know how to use a knife. You’re incompetent, and you’re painfully aware of it (as you ruin every other dish and keep cutting your fingers with your knife).

Eventually, you get to the point where you are consciously competent. You can cook, but you still have to think through everything you’re doing — how use the right amount of seasoning, knowing how long to cook things and in what order, how to prepare different marinades and sauces, etc.

Finally, through repetition, you become unconsciously competent. What that means is that you can cook without thinking about it. The actions just happen, and you can successfully put together stunning dishes while thinking about the toilet paper you need to stock up on soon because there’s another damn pandemic looming over you.

Everyone can relate to the feeling of being unconsciously competent at something. I’m unconsciously competent at typing this, and you’re unconsciously competent at reading it. But it wasn’t always that way. I used to have to search for the keys over and over, and at one point, you had to sit there and sound out each letter in a word to read it correctly.

However, unconscious competence does not come easily for any skill. There’s time and work involved:

- To go from unconscious incompetence to conscious incompetence, you must first gain knowledge and study the skill.

- To go from conscious incompetence to conscious competence, one requires practice and conscious effort.

- Eventually, unconscious competence happens through habituation: you’ve practiced something to the point where you don’t even think about it anymore.

- Then, you pick harder skills and repeat the whole process again, becoming better and better at your chosen activity.

But here’s where it gets interesting: what happens when we apply this same framework to something less tangible, like emotional development?

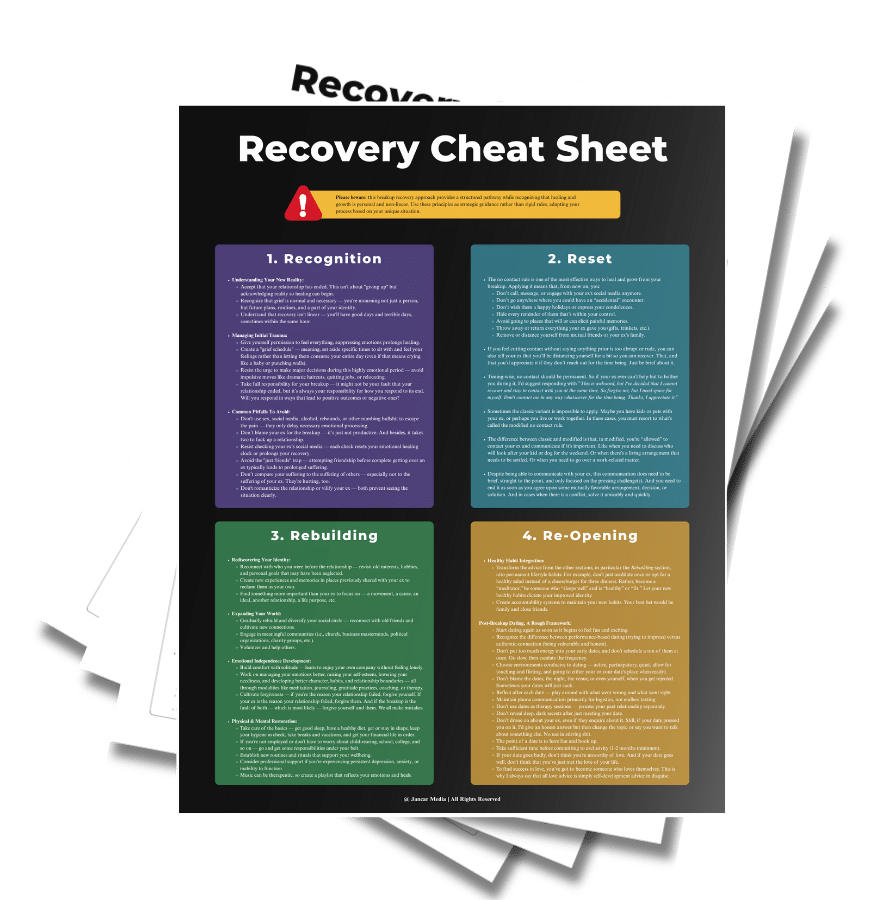

This cheat sheet lays out 40+ solutions to overcoming a breakup so you can create a new opportunity for love — be that with your ex or someone completely different.

Get The Free Cheat SheetModel For Emotional Mastery

My nerd theory is that the process in which we come to terms with our emotional problems follows a similar process to how we learn skills like cooking or typing. But before unpacking that, there are some key terms you need to know.

Compulsion refers to overreactions of negative emotions or emotions that cause you to pursue behaviors that go against your values or self-perception and that sabotage breakup recovery.

For instance, anger is a normal and healthy emotion that we all feel at one time or another. But getting angry at the slightest infraction and becoming uncontrollably violent is a serious compulsion, and it is unhealthy.

Regulation, in contrast, represents our ability to manage emotions appropriately to the situation.

For example, let’s say your ex doesn’t return your call. And as a result, you go into a screaming fit, call them up, and start threatening them. This is a compulsive emotional outburst and is a serious underlying issue that needs to be addressed. A regulated response would be acknowledging the disappointment or hurt while maintaining composure — a healthy expression of the same emotion.

Our emotions are also either identified or disidentified. This is where it gets a bit complicated and where my back-of-napkin theory kicks in.

My personal pet theory — and there is evidence for this — is that our emotions exist in order to protect our ego-identity. The problem is that when we form an unhealthy ego-identity, we begin to produce an unhealthy array of emotions.

For instance, if when you were young, you were always made fun of for being stupid, then you may internalize an ego-identity of being stupid and incompetent, even if objectively you are very smart.

The problem is that we adopt many aspects of our identities unconsciously or when we’re so young that we forget that we did. This is why a smart and capable person can have an emotional meltdown when presented with the smallest amount of intellectual stress. Or why a charming, attractive person can feel totally unworthy and desperate around the people they’re attracted to.

Their emotional reactions are compulsive. Because they’re unaware of why these emotional meltdowns are occurring, they are disidentified with them, as in, the part of their identity that is causing these unwanted emotional outbursts is unconscious.

So, the person who, deep down, believes that they’re stupid and incapable consciously does not identify with that belief. Or the person who is attractive but desperate does not consciously identify as desperate.

Still with me? I know this is getting a bit dense, but here’s where it starts coming together…

Once a person becomes aware of why their compulsive emotions are occurring (usually with the aid of some kind of therapy), then they can become identified with the compulsive emotions.

As they say, the first step to recovery of any kind — not just breakup recovery — is acknowledging you have a problem. So the desperate person comes to realize, “Hey, I’m attractive, but I feel desperate and pathetic around people I like romantically. Why?” Or the smart person who feels incapable finally admits and identifies with the reality that they are incapable of handling any intellectual stress or responsibility.

The hardest part about identifying with compulsive emotions is that we construct many beliefs and defense mechanisms to justify our compulsive emotions.

So, for instance, that smart person who has emotional meltdowns when presented with any intellectual stress may have convinced themselves long ago that people treat him unfairly and expect him to be perfect — that it’s not their fault they’re so stressed out all the time.

Or the desperate person may have convinced themselves that the people they find attractive only go for the most popular of men/women and you have to go the extra mile to prove how high status you are to them. These beliefs fall into place because they justify the compulsive emotions.

The Path To Emotional Regulation

Once a person has identified with their compulsive emotions, they must then learn to regulate them. The way to do this is paradoxical. Most people attempt to regulate their emotions through sheer willpower. Others try to find healthy ways to redirect their negative emotions.

These are forms of coping, and they are good short-term solutions but rarely make for good long-term solutions. The reason is that while they’ve gotten better at altering the negative behaviors that the emotions cause, the chunk of their identity that is causing the compulsive emotions hasn’t changed.

In fact, resisting negative emotions and fighting against them often strengthens them (evidence for this, too, by the way). As the Buddhist saying goes: “What you resist will persist.”

Compulsive emotions are caused by deep internal shame, the belief that we are not good enough or that we are somehow faulty. Research shows — and TED superhero Brene Brown says — that we undo our underlying shame by exposing it, accepting it, and even sharing it.

So once a person becomes aware of their compulsive emotions and the shame that underlies them, they must then accept it and practice self-compassion with the faulty part of themselves. I know “self-compassion” sounds like some fruity self-help nonsense, but here’s what it actually means: re-orienting one’s beliefs to understand and accept where the compulsive emotions come from (don’t worry, examples coming up).

Once one does this successfully, eventually, the compulsive emotions will become manageable and regulated. One will find oneself becoming less angry, less overwhelmed, less panicky, or less whatever.

And if one does become those things, it’s not the end of the world; they’re okay with it. They understand that they don’t have to act on them and, in fact, it’s far easier now not to.

But there’s one final step to truly breaking free from these old patterns: one must disidentify with the old compulsive emotions by sharing them and objectifying them through words. This happens through vulnerability.

You may actually recognize this process as being similar to what Alcoholics Anonymous uses. AA is actually surprisingly one of the most successful therapeutic processes in the world, despite being made up by a drunk with absolutely no expertise whatsoever. But that’s a story for another time.

The New Model

An online course that teaches you how to heal and grow from a breakup so you can create a new possibility for love — with or without your ex.

Get Instant AccessLet’s see how this emotional regulation process plays out in real life through two very different stories:

1. Sarah grew up with a single father who was unreliable

As a kid, she was often frustrated because her father seemed more concerned with his social life than her. She internalized an identity that she was not worth committing to and bolstered this identity with the beliefs that men are unreliable and untrustworthy. These were all unconscious. Or, at least, they happened so young that she forgot she had them and just always believed that’s the way the world worked.

In adult life, Sarah is a mess with relationships. While she seems abnormally preoccupied with dating and having sex with men, she finds herself either ditching the men immediately or the few she does become attached to, she becomes unbearably insecure and stressed around them.

To even notice these issues are going on, Sarah must be able to sidestep her personal beliefs about men and their trustworthiness and recognize her irrational emotional reactions to any man who gets close to her. She must perceive her own anxiety and stress, perceive her rationalizations for her behavior, and her apparent inability to secure intimacy.

Once she’s done this, she can identify as someone who has major attachment issues, and suffers through compulsive anxiety and stress any time a man gets too close to her.

Since Sarah is awesome and reads my blog, she recognizes that there’s no quick fix for her anxiety and that she must consciously face it head-on when she’s in these intimate situations. She accepts that she’s had an unfortunate emotional past, and she’s committed to changing.

As new relationships come up, Sarah doesn’t resist getting closer to men, although she doesn’t force it either. She feels the anxiety and faces the rationalizations telling her to dump the guy for stupid reasons or to run away. She accepts these feelings and rationalizations and slowly learns that they’re not necessarily true, and that they pass with time. She begins to find that some men actually are trustworthy and that intimacy can actually be far more pleasurable than mindless sex.

After many months and a few short relationships, she feels far more comfortable with the prospect of becoming attached and intimate with one man, something she’s never felt comfortable with before in her life.

She’s so comfortable now that she doesn’t mind sharing her problem with the men she dates, being very open about the fact that she used to have trouble with commitment and intimacy used to make her uncomfortable.

As she makes herself vulnerable and shares these emotional realities, she’s able to gain a third-person perspective on them — the former emotional issues are separated from her identity, and soon, she doesn’t even identify as someone who has intimacy issues, just someone who used to have intimacy issues.

2. Greg chronically feels unworthy

He placates everyone and is afraid to assert himself. He struggles regularly with depression and has a lot of self-defeating thoughts. Greg’s father is a popular politician, Harvard graduate, and successful at everything he’s ever done. Greg, on the other hand, had trouble in school, and every time he screwed up, he was compared to his father.

Greg internalized a lot of shame and constructed belief systems to cope with his feelings of inferiority. “Some people just aren’t talented,” he told himself. “I can’t help it if I’m not good at anything.”

But as life went on, Greg began suffering from unbearable depression. He was rarely motivated to do anything, and when he was, he always anticipated failure. Worst of all, his inability to hold a good job always landed him back at his parents house, being supported, again, by his successful father.

It was in one of these periods that he hit his limit. He signed himself up with a psychiatrist, was put on anti-depressants, and began seeing a therapist every day to talk about his issues.

The anti-depressants allowed him to separate enough from his beliefs and emotions that he could look at them objectively with the help of the shrink. He came to the startling discovery that a lot of his behaviors self-perpetuated his misery. It was almost like he wanted to be a failure and disappoint his parents.

He got another job, one that he wanted to do, not one his parents wanted. He began making good money and moved out of his parent’s house. He made a point to focus on new behaviors that would help build his self-esteem and create a life for himself, not for anybody else.

As he did this, he began to realize how much pressure he had always put on himself to do something that would make others proud. He also realized how hard he had always been on himself.

He identified these emotions and accepted them, acknowledging that they weren’t necessary anymore and that he could still love himself even if he felt like a failure or like he was disappointing someone. To his surprise, as his new life gained steam, his parents became emotionally supportive of him despite his unconventional choice of career.

Eventually, Greg is able to get off his anti-depressants. He still sees a therapist to keep him on top of his emotional issues, but he is no longer subjected to compulsive sadness. He’s disidentified from the depressed person he was years ago.

And for the first time in his life, he’s proud of who he is and what he’s doing with his life. He’s come to terms with his past and is more comfortable being vulnerable around others.

This comes in handy since his new job is acting in gay porn.

Tying Everything Together

Managing post-breakup emotions — or emotions in general — isn’t about suppression or forced positivity. It’s about developing awareness of your emotional patterns, accepting them, and gradually learning to regulate them in healthier ways.

Think of it as learning to drive a car. At first, you’re unconsciously incompetent — unaware of how bad you are at managing your emotions. You might not even realize you’re stuck in toxic patterns or making decisions based on unprocessed trauma. Just like a complete novice who doesn’t yet know what they don’t know about driving.

Then you become consciously incompetent — painfully aware of your emotional struggles. This is when you start noticing your patterns: the 2 AM angry texts, the spiral of jealousy when you see your ex’s social media, the way you keep telling yourself how you’re fine when you’re not really fine. Like a new driver who’s suddenly hyperaware of every mistake they make behind the wheel.

With practice, you reach conscious competence. You’re able to manage your emotions, but it takes deliberate effort. You catch yourself before sending that angry text. You recognize when jealousy is creeping in and consciously choose a healthier response. It’s like having to think through every single step of driving — check mirrors, signal, check blind spot — you can do it, but it requires your full attention

Finally, you develop unconscious competence. Healthy emotional responses become your new normal. You naturally process breakup emotions without letting them control you. Just like an experienced driver who smoothly navigates traffic while carrying on a conversation — it just flows naturally.

Will this process be comfortable? Hell no. But it’s far better than letting unmanaged emotions drive you to make decisions you’ll regret — like drunk-dialing your ex at 3 AM, stalking their new partner on Instagram, or writing a novel-length comment on their TikTok about how “happy” you are without them.

Bottom line: your emotions aren’t your enemy. They’re simply signals trying to protect you. Learning to work with them rather than against them is key to healing and growing after a breakup. That, and simply becoming a better, more rounded, and mature person.

This cheat sheet lays out 40+ solutions to overcoming a breakup so you can create a new opportunity for love — be that with your ex or someone completely different.

Get The Free Cheat SheetRelated Reading

- How To Love Yourself After A Breakup (7 Realistic Activities) November 20, 2021

- 7 Strange And Unexpected Benefits Of Sadness October 19, 2022

- 6 Myths About Emotions (And What To Believe Instead) March 4, 2022

- Finding Hope After Heartbreak May 26, 2020

- 8 Ways To Overcome Anger After A Breakup October 22, 2021

- Radical Acceptance In The Face Of Adversity February 5, 2022